Resilience is a documentary film about adoption, focusing on the reunion of a Korean mother and her son.

Directed by Tammy Chu, and supported by various elements in the Korean adoptee community, it was filmed over a period of four years. Our friend Widhi, my wife and I went to see a screening in Anguk last weekend. Following are our three opinions on the movie, beginning with brief profile backgrounds.

______________________________________________________________

Lee Farrand (이소하): A 28 year old Korean Australian, adopted to Australian parents at the age of 2. Returned to Korea in 2006 and is currently a PhD student at Seoul National University, studying ovarian cancer. Tried briefly, but was unable to locate birth parents.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Lee: I had intended to see Resilience for quite a while, mainly due to the increasing amount of times it popped up in the adoptee online community. But a busy schedule and a general deprioritising of all things adoption-related for the time being, led to me listing it as a non-urgent matter on my mental list of things to do. Then a couple of weeks ago, Nanoomi, an English K-blogging initiative, mentioned it on it's discussion boards. Before long, I had found myself cyber pinky-swearing to do something that in retrospect I'd rather have let someone else do. Reviewing movies is always fun, but when the topic is adoption, I find myself having difficulties expressing my thoughts with clarity.

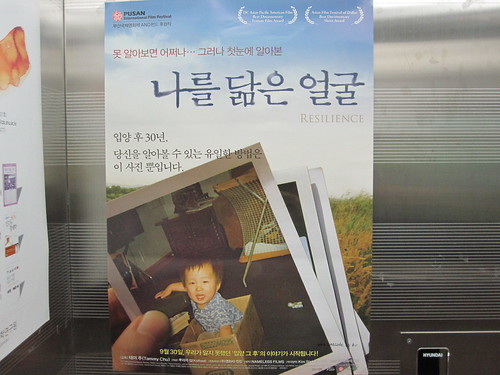

And then up flew a poster in our Biomodulation department elevators at university. I took this as a sign to get my act together and go see the film while it was still playing. While I normally enjoy an insulated life on campus, it seemed that Resilience was creating waves from somewhere north of the Han River, and tiny ripples were lapping at my shores.

How does an adoptee put in words, the work of another adoptee that focuses on the topic of adoption? Describing the film in aesthetic or technical terms would, for me, seem to be side-stepping the core issues. These issues are specifically relevant for anyone affected by adoption, but perhaps just a passing curiousity for those who have not.

My initial reaction to Resilience was a mixture of feelings. I felt a little inspired, a little helpless and a little angry.

The documentary follows the lives of mother Myunja Noh and her son Brent Beesley, separated soon after Brent's birth due to family problems. Brent's Korean father gambled the family's savings away, and ended up leaving. Myungja's family put Brent up for adoption without her consent, and she returned to pick him up one day, only to find that he had been sent away and and her relatives refused to tell her where her baby was. Brent ended up being adopted through an agency, to a family in a small country town in South Dakota.

Brent returns to Korea alone, with two daughters back home, looking for his birth parents, partially out of curiousity and partially for the family's medical history. He and Myungja meet for the first time on a Korean TV show that specialises in reuniting family members. For many adoptees, going on national TV is their last ditch effort in trying to locate their birth parents, when all other options have proven unhelpful. While the utility of this particular show has been remarkably successful, many adoptees including myself would only consider appearing on it after an excruciating amount of consideration. After all, who wants their first meeting with their birth parents to be hijacked by the spectacle of a Korean television show? It's like giving someone's eulogy while dressed up as a clown.

Before meeting his mother, who is kept behind a curtain, Brent is asked by the show's host to write on a piece of paper whether he 'forgives' her or not. Asking a son to forgive a mother he has never met, for circumstances he has yet to even learn about, is a little ridiculous. After all, no sane person would go to all that effort to appear on public TV for the sole purpose of shaming their birth mother. I guess the TV show executives need to make money, but perhaps the subject matter could be treated with a little more graciousness.

The documentary then focuses on what happens after reunion, which is often a complicated chapter in the lives of both parties. Resilience maintains a fairly neutral perspective, and both Brent and Myungja's natural behaviour and openness about their feelings provide a firm foundation for the film's substance.

Brent talks about his upbringing in a white American family but as a racial minority, a common experience for many transnational adoptees. As an idea lingering in the background during childhood, his reflections describe adoption as being neither a distinctly positive or negative experience, but that he had a good life nonetheless. After meeting with his overwhelmed mother, he is abruptly forced to react and respond to a surreal change in his life's events. These include being smothered with attention and being almost forcibly assimilated into Korean family life. This occurs at an accelerated pace, as if to be making up for lost time. Myungja works in a restaurant and does not have a lot of money, but most determinedly decides to buy gifts for Brent and his family members. These include expensive Korean hanbok, that Brent neither needs or wants, but accepts on occasion for the sole purpose of letting his birth mother know that her expressions of affection are appreciated.

Myungja comes across as a warm hearted and sensible Korean mother, plagued with a seemingly incurable amount of guilt that drives her daily life. She describes her difficulties in expressing her true feelings to Brent without a translator, and her eagerness to build a strong relationship with him. In some ways it seems as if she is a little frustrated that Brent does not behave in a typically Korean way, but this is always swamped and overridden by her inner determination to compensate for time that has been lost.

The documentary itself combines an interesting mix of elements. Filmed over the space of four years, with Brent traveling back and forth between the US and Korea, it uses passive recording of family gatherings, interviews with family members and even self-recorded video blogging to communicate the complex balance of feelings on both sides of the Pacific.

As an adoptee myself, who has been living in Korea for some time now, I felt intricately connected with the unfolding story. Brent's description of his upbringing, from the Bruce Lee references by the kids in his neighbourhood to his family photos surrounded by a white family are highly familiar to both myself and many others. Similarly, upon his return to Korea, the culture shock of the Korean way of life is also something I can strongly relate to. Brent describes Korean families as being 'tribal,' something I find to be both a positive and negative aspect of life in Korea. Western families tend to have more physical and emotional distance between individual members, something that comes with a higher amount of personal freedom. Brent is strongly encouraged to learn Korean (his mother reads him the alphabet), and become 'more Korean.' This is a common theme arising after family reunions, which is an extensive cause of frustration on both sides.

Adoptees who have grown up overseas often have trouble integrating into Korean society, which is not a result of personal desire alone, but because of the irreversible formation of an identity in another country. As such, we often find ourselves having to defend our individual tendencies. This ranges from why we don't study Korean 'with more passion', to why we don't think that age alone is an appropriate reason to respect someone. As a Korean adoptee, I feel neither completely Australian nor completely Korean. I don't like speaking in Korean, and I don't like eating ddeok. Nor am I particularly interested in Korean history. But at times I do appreciate the accelerated closeness of Korean friendships and I admire the fierce aspirations of the Korean people. And I also feel genuinely happy when Korea does well in the World Cup. But the same is true when Australia does well. Being tied to both of our mother countries is an integral part of who we are, and the amount to which we feel closer to one or the other should be left for us alone to decide.

Seeing Resilience, I find it difficult to not talk about my situation, and express some of my own thoughts on Korean adoption. When it comes to the idea of adoption, I don't think anybody has the answers, nor can anybody accurately represent the opinions of all parties involved. For myself, I do have some opinions on how things could be more fair and more logical. Much of this has to do with aspects of Korean society and social norms that are followed here without reasonable analysis or discussion.

Many advocates have long been convinced that a large part of the remedy would be the evolution of women's rights in Korea. This includes everything from healthy public debate about a woman's right to make a conscious choice about maternity, to workplace discrimination and pay differences according to gender (Korea ranks unfortunately lowest in the OECD).

The lack of women in CEO and management positions in Korea is representative of a wider social disparity. The actual ratio for male to female professors at SNU is likely to be abysmal - after 2 years at the university, I've still never met a single female professor in person. Incoming professors in our department are voted in by a special board, made up entirely of older males. There could also be more support for single mothers, including an expansion of maternity leave, and anti-discrimination laws regarding employment. Without massive support from friends and family, and an inadequate system of welfare, a single mother in Korea has little chance of living a successful life. For all its progress in leaps and bounds, Korea still has strong social forces of conservatism that are holding it back.

Filial piety (효), a term barely recognisable in the Western world, refers to the Confucian belief that respect for one's elders and ancestors is a virtue to be held above all else. While questionably reasonable (if one has respectable elders), in Korean family life it is heavily enforced as a necessary path to a virtuous life. In a simple world, such a virtue may seem worthwhile, but in modern Korean society its side-effects include the abuse of power, unfair discrimination and the sidelining of logical debate.

Filial piety encourages the surrender of individual will to a collective conservatism and an unquestioning defense of the status quo. This quenching of respect for the rights of the individual in Korea, for what is disguised as the collective good, often allows elder family members to make extremely important decisions without consulting those who would be most affected by them. In Resilience, Myungja talks with clear bitterness about how her family members sent her son away while she was looking for work, and refused to tell her what had happened. The decision for the family members must not have been an easy one, and we can conclude that it may have been in everyone's best interests. However, Myungja's acceptance of the unfair, even after all these years, may seem quite unsettling to an outside observer. The drive to endure and persevere 'diligently' in the face of injustice is deeply rooted in the Korean psyche.

People who openly criticise these aspects of Korean society, soon find themselves at odds with blind patriotism and a strong defense of things unreasonably defined as a part of the Korean identity. This is a reaction not unique to Korea, but common in all societies that have an underdeveloped realm of public debate. Korea has come a long way in these past few decades, and a helpful next step may be to grow up from its patriotic origins and focus on facing ethical issues with logical maturity.

After seeing Resilience, it's got me thinking again about my own birth parents. A birth search costs not only time and money, it's psychologically draining and the emotional risks are extremely high. I've been married to a wonderful Korean wife for over a year now and we live in the international dormitories at SNU. My wife is now 10 weeks pregnant, and after she gives birth, we'll be living off my scholarship and my part-time tutoring job. Life is busy and not always easy, but we are both happy. But I realise that right now, before we have our child, is the best time to start looking again. In some ways I dislike feeling rushed to do something that I'm not sure I'm ready for.

In conclusion, Resilience is an impressive piece of work, and its distinct elements make it uniquely recognisable as directed by someone who has an inseparable relationship with, and passion for, the subject matter.

While it doesn't end with any concrete conclusions, it's likely to arouse ripples of thought and discussion among both adoptees and Korean citizens alike, which will hopefully become a catalyst for fair and logical future changes.

______________________________________________________________

Heather Jung (정가희): Lee's wife, a 30 year old Korean native from Busan. They have been married for over a year. Currently employed at an English language school in Seoul

Heather Jung (정가희): Lee's wife, a 30 year old Korean native from Busan. They have been married for over a year. Currently employed at an English language school in Seoul-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Heather: I had earlier watched the movie 'Susan Brink’s Arirang' in 1991, which describes the life of an adoptee girl, Susan, who had a tough life since she was adopted to Sweden when she was 3 years old. The movie ends with a scene showing Susan meeting her biological parents. It seemed that the Korean audience was moved by such a dramatic story.

The movie begins with the reuniting of an adoptee and his mother, which was how Susan Brink’s Arirang ended. It was interesting because it didn’t completely look like someone else’s story, and somehow related to me, because I had heard many stories about adoption and adoptees from my husband. I can only guess how they feel upset when they realized their lives were twisted from the beginning.

My husband and I agreed that the case in the movie is one of the better-ending stories which may not always happen. However, it is still mixed up with small conflicts between a mother who was missing her son for 30 years and a son who has grown up in a totally different environment, not knowing anything about his biological family. People tend to think that if adoptees find their family, they can fill up the last piece of the puzzle for their lives. But they may feel even more dejected when they discover unexpected gaps between them.

Both Susan and Brent reunited eventually, but it will take a long time to fill the gap between them and their family members. Because of that, adoption and reunion can be a more difficult story than we first expect.

Both Susan and Brent reunited eventually, but it will take a long time to fill the gap between them and their family members. Because of that, adoption and reunion can be a more difficult story than we first expect.

______________________________________________________________

Sriyulianti Widhiarini: An international student of aerospace engineering studying at Konkuk University from Bandung, Indonesia. Has a strong interest in the independent music scene in Korea.

Sriyulianti Widhiarini: An international student of aerospace engineering studying at Konkuk University from Bandung, Indonesia. Has a strong interest in the independent music scene in Korea.-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Widhi: It was not the adoption theme that brought me to watch the movie, but I was actually interested to watch the movie because of the band Dear Cloud’s song ‘그럴수만 있다면', that was featured in it. The trailer seemed to be very promising and the music fits very well in it, so I decided to give it a go without any hesitation. It was a very nice opportunity that I got to see it with Lee and his wife Heather.

It was very interesting to see how a 4-year story was put together in a merely 95 minute movie. The story itself was very interesting and the stories were smoothly delivered scene by scene. The background music was also put at the right scene without making it too dramatic or bland at the same time. It was a little bit emotional for me after the first half of the movie. However, it did not last long since the movie moved very fast and I no longer could hold that particular emotion for a long time.

Adoption has never been a very familiar thing for me. By watching this movie, I see an example of how it is not always about ‘living happy ever after’. There is always a void in the heart of an adoptee when he realizes about his true identity, especially when it comes to international adoption. There is always a question of ‘why’ and the eagerness to find the answer. It might have also been painful for those who later realize about the true reason of why they were adopted. This movie may serve as an example of a happy story, yet I thought of the opposite at the same time. It was merely being emphatic yet I really could not go deeper than that.

Somehow I felt that the movie itself showed merely a balance of happy and sad, while other emotions like anger, confused, curious were rather less apparent. Yet, since a lot of scenes involved talk or conversation, the instrumental music fit very well with each scene and I could feel a glimpse of longing. It was not until the end of the movie that I finally heard the song from Dear Cloud. For me, it closed the movie quite well. I was kind of hoping that the song would come out a little earlier in the movie but I realized that it would have somehow mixed up the story within the scenes.

The title of the song itself ‘그럴수만 있다면’ means ‘If I Could’ and may perfectly portray the desire of the two main characters to know more about their past. It’s related to the movie and does not look back merely at the past but also tries to give more focus on what is coming in the present and future. What becomes the last word of the song ‘끝나지 않는 꿈’, means the story has yet to finish but it is also an unfinished dream, especially for both of the main characters.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Resilience is now showing in selected Korean cinemas. For more information, please refer to these links:

http://www.resiliencefilm.com/

http://www.koroot.org/

http://www.goal.or.kr/

11 comments:

This has been an interesting topic for me for a while. In a past life I used to be a Taekwondo instructor in America. I'm white but my bosses were Korean. I taught a lot of kids who were adopted. Tae Kwon Do was kind of a means for the kids to learn a little bit about Korean culture, but it never really taught much about Korea. Nonetheless, I think kids can get a pretty good impression of Korea from practicing Tae Kwon Do, if they have a responsible instructor. (Much better than say the expat blogosphere.)

There was also a Korean church in my town that had Korean classes, but that church was super fundamentalist. My Taekwondo instructor's family was Catholic, and she said that when her son went to that church to learn Korean they tried to convert him.

Anyway, now I'm here and I have a Korean wife with a little Korean Pollack on the way, and all I want to do is have a kid with self confidence and a strong sense of self. I don't want the kid to think of himself as half Korean and half American, I just want him or her to be proud of themselves as a person. Korea and America are both rabidly nationalistic countries, and I want to protect the kid from developing any kind of trauma of self identity. Now that is easy for me to say because I'm an American man of mixed European ancestry, and I guess I'm already projecting my cultural bias by hoping that the kid sees it's self as a competent individual rather than someone who has to submit to the community, so damn it'll be interesting. I wonder if people who were adopted have any insight.

Great post. Loved reading your perspective on the film, and I think you did a great job expressing yourself. I saw it a couple weeks ago and didn't talk about it for the same reason you mentioned... too many thoughts and absolutely no clue where to even start. Actually, if you don't mind, I'm going to link to your post on my blog. I think it's well-written and also gives a deeper look into the Korean psyche. It's something to this day I can't wrap my head around. Actually, the part about the filial responsibility made a light go on in my head. It was like I'd heard about it, but until I read your explanation, it never struck me just how important this concept is to Koreans (and how much it affects their daily lives).

Anyway, thanks for the post.

Interesting situation 3gyup. I think the best thing to do is keep an open mind and play your part as best you can.

Hi Kim! Glad you liked it. You're more than welcome to link anything on this blog. We should make a beer appointment.

Loved it. Thanks Lee!

Family preservation should be the the main emphasis so international adoption is definitely not the answer. I agree with you that more social welfare is needed for single mom. Abandonment should also be made illegal. As for filial piety, it also can use some western influence.

Lee and Heather - I love you guys!

Lee- great post! Well-written and insightful. You explained aspects of Korean society quite well and the things that needs to be changed... I am so glad to see that the film has sparked some discussion. Thank you also Heather and Sriyulianti for your comments about post-reunion and the music!

Thanks Tammy! It was a great film. I've heard that this post is going to be translated into Korean and posted on some other blogs. I'll send you the link if it happens.

That's awesome to hear. Congrats! :)

Thanks for this post Lee. And to Heather and Sriyulianti. The last bit of what Heather said is really food for thought.

Beautiful post Lee. I'm an American Mom of two wonderful Korean boys. I particularly appreciated your description of how you don't quite feel 100% Australian or Korean. During our adoption process I learned alot about the social issues that result in international placements, but you gave another very clear explanation and added more insight into the Filial Piety aspect. Thank you!

Post a Comment